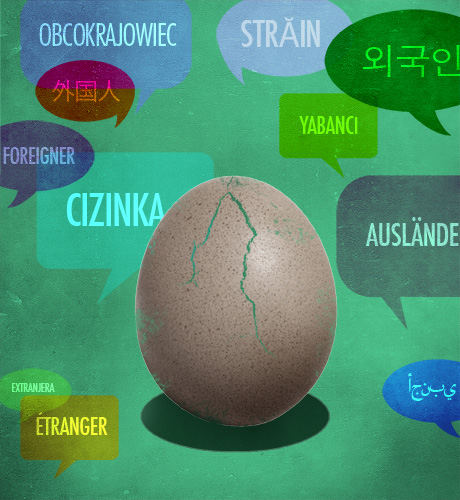

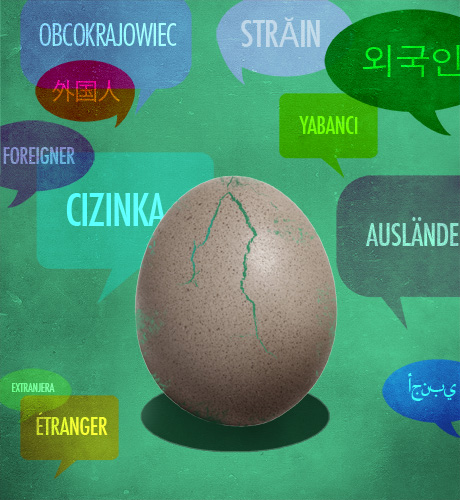

Illustration for Denizen by Elaina Natario

It began as a lovely evening: a room full of cheerful Czech strangers; my close friend Karolina, who I was visiting in Prague; a table laden with roasted pork, fresh brown bread, apple-horseradish salad, and spicy mustard. I was handed a Pilsner-Urquell, a plate heaped with food, and offered a chair among Karolina’s friends, all artists, musicians, and writers. I felt in my element: visiting a foreign city, catching a glimpse of local life.

Until I realized this was a Czech party. By “Czech” I don’t mean everyone there was Czech, which was great, but that everyone was speaking Czech, which was not so great. At first, I tried to ignore my discomfort by observing my surroundings, taking in the other guests, concentrating on the delicious pork. But the food began to taste like sand as a larger sensation swelled inside, dimming the light in the room, making the raucous laughter sound cruel, and most embarrassingly, causing tears to prick my eyes.

Another punchline, and the circle roared. I looked on longingly, like staring at a warm fire from the snow outside. I was aware that my reaction bordered on melodramatic. Really? I argued with myself. A warm fire? This is a party, for God’s sake, not a Charles Dickens novel. Didn’t you grow up overseas? Can’t you handle this?

But that was precisely the problem. It was an all-too familiar pain, a broken bone that had never healed right.

Foreigner! I am in Shanghai, 12-years-old, the only white person on a Chinese basketball team, the subject of hilarity as I run the wrong way on the court, having misunderstood the instructions, related in speedy Shanghainese. Bun dan! the coach shouts at me, and my teammates giggle shrilly. Even though I don’t speak Shanghainese, I understand what my coach said: bun dan: stupid egg. I run back, my face burning, and stifle my urge to run away from practice, out of the school gates, down Nanjing Road, back to the safety of my family’s apartment. Or even better: across the Pacific Ocean, across the continental United States, back to Atlanta.

But I just step back in line. I’m here to make my dad proud, to be a “good ambassador,” to banish the weak feeling inside, the one that won’t stop moaning I hate this. I want to go home. I fake a smile, wait my turn, and perform the drill, heading to the correct basket this time. The coach gives me a big thumbs-up when my layup goes in. But my flash of happiness doesn’t soothe the bigger gnawing inside, and his echoing words. Bun dan. Stupid. Foreigner.

Seventeen years later, as the Prague party continued, I went into wallflower mode. During a pause in the conversation, I attempted to speak to my neighbor in English, which worked until she got up and left. It’s no big deal, I told myself. They don’t mean to leave you out. It wouldn’t make sense for them to switch to English; don’t be an ugly American.

But what did everyone think of me sitting there, so obviously uncomprehending? Then I remembered: they didn’t see me. Caught up in the midst of an anecdote about that concert in Moscow, the black hole I was falling into was invisible to everyone else, including Karolina. And what right did I have to spoil everyone’s good time? But a voice inside insisted, I hate this. I want to go home. Thirty minutes later, I turned to Karolina, and said, “I don’t understand a thing. Can we go now?”

Mulling over the night now, on the train from Prague, I’m not sure what I should have done differently. Should I have told Karolina that I didn’t want to go to the party, and missed out on an “authentic Prague experience?” Should I have complained about it to her immediately, and insisted that we leave? Should I have strong-armed the group into speaking English?

All of these options seem unsavory, and lead to some larger questions: If I really want to avoid nights like this, wouldn’t it be better to live in the ‘States? If being a foreigner hurts so much, what am I doing settling in Berlin? The whole set up is a recipe for alienation.

But the alternative is equally untenable. I may look and sound American, but I crave a life overseas, which is how I grew up—living abroad is just as much a “home” to me as my grandmother’s house in the North Georgia mountains.

I think the answer lies in silencing my basketball coach’s voice in my head: Stupid. Foreigner.

Once he’s quiet, the chatter in the room may still be unintelligible, but at least it won’t sound like existential unbelonging. And before the internal drowning begins, I might learn to stand on the ground inside me, the one packed down with the dirt of so many countries. It sucks to be left out. But that’s also a part of being a foreigner, the life I chose. And I can choose now, too, to tell the coach in my head to shut up. With that accusation lifted, I can listen to a softer, gentler murmur inside.

Because not speaking a language should never mean losing your voice.

Love this 🙂 .. even worse when people assume you don’t know their language just because you’re not “like them” and talk crap 😛

LikeLike

wonderful piece. you captured exactly how i felt living in shanghai, that feeling you get as you look longingly at the laughter around you, wishing you knew what the hell what going on. thanks for writing this piece… i loved it.

LikeLike