I’ve flown across the Atlantic so many times that I’ve lost count, so often that the journey is like my early morning stumble from bedroom to shower. But I remember the first time.

It was 1985, and I was five. I held my mother’s hand as we boarded the plane at O’Hare, and the stewardesses smiled at my Laura Ashley dress and patent leather Mary Janes. My sister Margaret* was three, and dressed just like me. On that journey we were happy and well-behaved. Dad had landed a job with the U.N. after answering an ad in the Wall Street Journal. We were moving on up, abandoning the grey suburbia in Illinois for Rome (“Ro-ma!”).

My sister Alessandra was born in Rome six months after we arrived, and our lives in Italy lived up to her elegant Italian name. There were international schools and embassy parties. My father’s office had a view of the Circus Maximus.

“You are walking in the footsteps of Julius Caesar, girls,” Dad said.

At school, our classes were half in English and half in Italian. Within months, Margaret and I could prattle away with our Italian babysitter Emmanuela in her native tongue. My hilltop elementary school stood on the grounds of a former vineyard, and counted three Borghese scions as members of the student body.

Six years later, when my parents split, my sisters and I moved back across the Atlantic with mom to her hometown: Kalamazoo, Michigan. By then, it was the States that felt like a foreign country. We were different in the ways that mattered, from our too-short pixie haircuts down to our Superga sneakers, so out of place amongst the stampede of Nikes. We spoke funny, our English interspersed with Italian–instead of ouch, we said “aia.” We measured our height in meters and our weight in kilos. Though we knew other kids whose parents were separated, no one’s father lived in another country. My classmate Henry threw paperclips at me.

“Go back where you came from!” he snickered.

It didn’t help that as soon as summer arrived, my sisters and I did go back. My father had fought for joint custody, and won. So even though Dad lived in Italy, we were expected to spend a good amount of time with him each year. And we were expected to travel alone across thousands of miles to do so. Every summer, and every other Christmas.

The trips became routine, and we sleepwalked through them. In Kalamazoo, Mom took us as far as the American Eagle gate at the airport, and then waved goodbye as we boarded a puddlejumper to Chicago. We’d board another plane at O’Hare, which would carry us to an anonymous European hub. Once in Europe, we would connect to our third and final flight of the journey. Dad would meet us in the arrivals lounge at Fiumicino.

“Hello, girls,” he’d say, like he was picking us up from school. Safely in our father’s custody, we’d yank off the packets hanging around our necks, which stored our passports and announced to the world that we were “Unaccompanied Minors.”

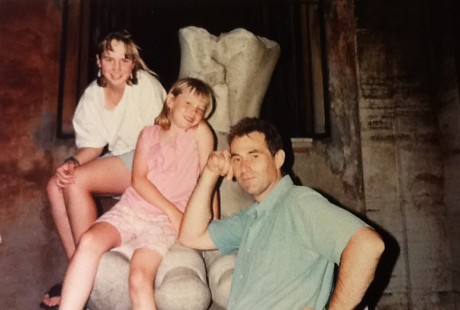

Me, Alessandra and Dad, 1993

Because I was the oldest sister, I was, by default, in loco parentis for each of these trips. But no one told me one key fact about traveling with young children: they puke. Each time a flight took off, and right after it landed, Alessandra, six years younger than me, threw up. She puked when we taxied on the runway in Frankfurt, and when we took off in Brussels. She puked while we idled on tarmacs in London, Chicago, New York, Venice and Milan. She’d often puke right into my lap. She announced the puke’s imminence with a quiet “it’s coming,” as though it were a check in the mail. It was my job to have the sick bag ready. It was also my job to hand the bag, full and dripping, to whatever flight attendant made the mistake of checking in on us. A few times I was too embarrassed to hand it to anyone, so I tucked the bag and its brimming contents into the seatback pocket, behind a magazine. After those flights, we hustled quickly off the plane.

During this “every summer and every other Christmas” era, my sisters and I stayed with Dad at his bachelor pad in Trastevere, a bohemian neighborhood that hugs the Tiber. You orient yourself in Trastevere based on which bridge you are near—the Ponte Rotto (the “Broken Bridge”), the Ponte Sisto (direct access to Campo de Fiori and Italian teenage boys), or the Ponte Inglese (the “English Bridge,” because traffic flows in the wrong direction). Every corner of Trastevere was a postcard, its cobble-stoned vie lined with pizza and gelato. We’d sit on the steps of the fountain in Piazza Santa Maria, gobbling ice cream out of paper cups and staring at the good-looking teenagers draped in elaborately-knotted silk scarves.

Dad’s place was on the fifth floor of a building near Santa Cecilia, whose bells rang each morning at 7. There was no elevator, and, for a few years, no dining table. Not the ideal place to host little girls. There was a sense of anarchy to the months we spent there, and Dad imposed no rules to govern the daytime hours he was away at work. Instead, he encouraged us to explore Rome on our own. He’d give us some Lire for food, and that was it.

By the time Margaret and I were teenagers, we decided to stockpile the food money. We’d figured out there was no drinking age in Italy. On the last day of our visit we’d scamper to the liquor store on Via della Scala and blow all the Lire on Absolut to bring into the United States.

Margaret was pushing six feet by then, and she and I looked less and less like girls, which meant that our carryons might be inspected at Fiumicino. Or worse, at the customs checkpoint at O’Hare.

“My backpack is really heavy,” Alessandra complained while we stood in line at the Fiumicino security check. She was 9 the first time we used her as our booze mule.

“Shhh, Ale. Be quiet,” Margaret growled. If the plan worked, only Margaret and I would be asked to open our carry-ons, and little Alessandra and her backpack full of vodka would sail through unexamined.

Did it work? Every time. For a few weeks we were heroes back home, and the vodka flowed freely in clandestine basement parties across Kalamazoo.

But it was no great feat to smuggle it in. Alessandra, gap-toothed and pigtailed, looked every bit the innocent. No one wanted to examine our bags, to bother us. They seemed to know, instinctively, that kids traveling such long distances alone are shuffling from one parent to another. We’d get sympathetic stares and pity-filled nods from the flight crew and fellow travelers alike. Every summer, and every other Christmas, we marched through one gate after another, soldiers of separation, casualties of a difficult divorce.

Me and Alessandra in Rome, 2007

As a result of all of this flying back and forth, my sisters and I are permanently out of place. There’s still something a touch foreign to the way we speak “American,” and no matter how good our Italian accents are, because of our hair color and American dress, we will always be “straniere” (foreigners) when we buy pizza in Rome. At the same time, we are all expert travelers. I’ll go anywhere, whether or not someone can go with me (when no one was free the week I wanted to go to Colombia, so I spent a blissful week in Cartagena on my own).

This sense of being adrift kicks in hard around the holidays, even though I’m married now. In the absence of a mandatory, court-ordered trip to Rome, I really don’t know where I’m supposed to be. I wish there were some routine, some place I knew I was supposed to return to. Maybe that will happen when I have children of my own. Until then, I’ll always have the international terminal at O’Hare, which always makes me think of Christmastime.

*name changed by request

Wow. Thanks for sharing your story, and for sharing it with humour. It is known that TCKs can be restless(I have that too) and have a desire to travel but reading your story I can see that it is even more complicated.

LikeLike