“What’s geography?” Vincent asked as he looked up from his journal assignment. It was the second week of school, and I glanced up from my attendance sheet to gauge the seriousness of the question. I assumed my ninth grader was joking.

“What?” I asked.

“What’s geography?” The blank look on his face told me he was dead serious. I looked at the board where I had posted a prompt asking students to write about the importance of geography.

“You know, geography,” I stammered. “Mountains, trees, rivers… what you see around you.”

Vincent stared back at me like I was speaking a different language. In an instant, the confidence I had built up from four years of education studies evaporated. I looked at the other faces of my ninth graders peering up at me, a strange woman who claimed that she had traveled the world before coming to small-town North Carolina.

They had no idea what I was talking about.

For the rest of the week, I mulled over the experience of that morning’s geography “lesson.” I thought back to my own education in Taiwan, and remembered memorizing the countries and capitals of the Middle East in seventh grade. Early on, I had become adept at pointing out where Taiwan was located so that I could help my American friends understand a little bit of my TCK background. Geography had always been such a natural part of my education, and yet my students didn’t know what it was.

As I thought about that experience, though, I returned to the old adage that my education professors repeated over and over again: so many times, students teach their teachers more than teachers teach their students.

I had just learned lesson #1 from my students: being a TCK had afforded me with an invaluable education. While I had been taught by passionate and skilled teachers, the diversity of countries in which I lived, and necessity of skills to navigate a varied cultural experience made me ready for the world as an adult.

I tucked this lesson in the back of my mind. A few weeks later, the day before the deadline of a major project, Jessica came to class early.

“Ms. Owen, I don’t want to present my project,” she said to me.

“Why not?” I asked.

“I don’t want to,” she said. “I’m not good at talking, and I don’t like the way other people respond.”

I’d seen it before in some of my other classes—so many of my students were scared to get up in front of their peers and share something that they had put time and effort into.

“I know you’re a talented young lady,” I told her. “Sometimes people aren’t going to understand us the way we want them to. You have something to say to the world, and I want you to be proud of that.”

She didn’t seem to buy it. As a TCK, seemingly everyone around me had pumped my classmates and me full of the conviction that we had something to say. We were young people who, in our comparatively short lifetimes, had done and seen more than the average suburban resident. They told us about our different perspective. They told us about the diversity of our experiences. And as a result, we believed that we were worth something. I did not know how much I had carried that conviction with me through college and into my career until I discovered my students did not have that belief. Jessica had unknowingly held a mirror up to myself to teach me the second lesson I would learn from my students.

As the year continued, though, I recognized how this pride and confidence had, in turn, allowed for the development of other key skills. Because I knew that I had something to say to the world, I could more easily grasp the fact that other people might also have something to say. My mother made sure of this early on.

When we were young, we attended a religious service we had never seen before. My brothers and I sat on black vinyl chairs, swinging our legs, looking around for a clock. When we looked up at the action taking place in the service, we saw people falling down on the ground, momentarily lost to the world. The word “stupid” must have slipped from one of our mouths, because the next thing I knew, mom was whispering fiercely from behind us that being different did not make something stupid.

That stuck with me. And with that understanding came a realization that not everyone was going to always see everything the same way as me. It in no way minimized my perspective, but reinforced that other people’s opinions held just as much bearing as my own.

So when I asked my ninth graders to consider both the pros and cons of a Medieval leader converting to Christianity, I realized again how fortunate I had been. As I posed the question, I immediately received an emphatic response: “Convert to Christianity!”

“Why, Daniel?” I asked. “How will it help you as a leader?”

“Because Christianity is right!”

I smiled at his unwavering devotion to his Southern heritage, but hoped that one day I could show them the value of understanding alternate perspectives.

Watching my students every day often makes me smile, as they seek to build skills and understand what Olaudah Equiano intended in his autobiography. Sometimes, though, my smiles turn to bewilderment as I see my students come a problem in learning and halt. Not stumble and keep going, but come to a full and complete stop.

“Why didn’t you come after school yesterday?” I asked Fred when he didn’t return to my classroom after discovering the library was closed.

“I forgot my flash drive,” he told me.

I smiled, encouraging him to some the next Tuesday so we could work on another part of the project. From “I don’t have a pencil” to “I don’t have a computer,” my students’ problems often seem insurmountable to them. Being a TCK had thrown a number of problems at me, but whatever form that problem took, I made it disappear as quickly as possible. When I stood alone in an airport flying by myself as a teen, I made sure I got to my gate. When I couldn’t understand the Chinese on a piece of mail I’d received, I made sure to track down someone who did. Watching my students showed me how much I wanted to teach them that their problems were worth solving themselves.

From having confidence in my voice to understanding that diverse perspectives are important, every day when I go to school, I hear my students telling me how blessed I am to have had a TCK upbringing. Unfortunately, the reality is that many of my students will probably never leave the state of North Carolina to be able to experience the diverse education that I received—which means that I have the responsibility of teaching beyond the textbook. One March day as we delved into the journeys of explorers discovering the New World, my student Timothy spoke up.

“How can you discover a new land if there were already people living there?” he asked, referring to Christopher Columbus and Native Americans.

As I threw the question back to the rest of my students, I realized that one of my greatest hopes for my students was becoming a reality. As they spoke, they carefully considered the importance of different perspective in defining history. The weeks I had spent walking them through the different backgrounds of historical figures were finally paying off.

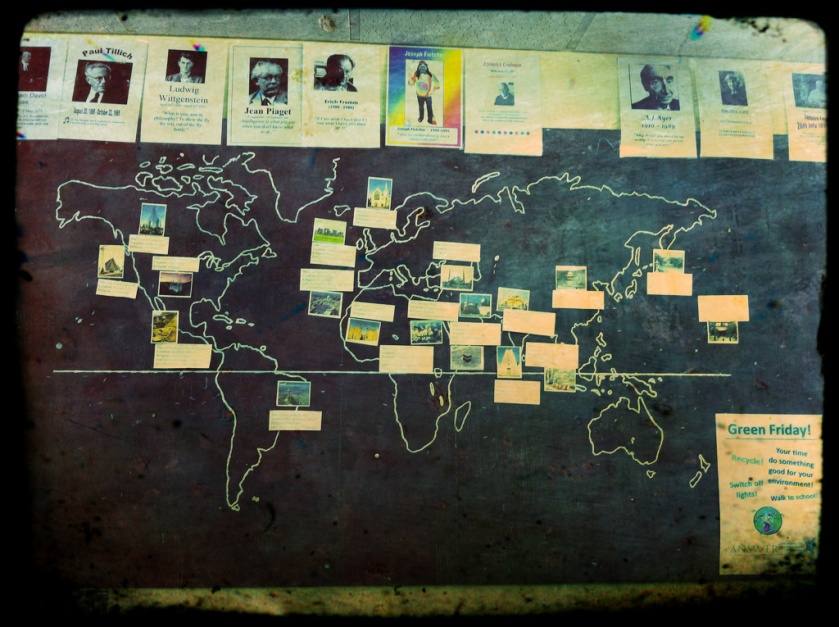

The lessons my students have taught me have shaped how I teach them. When my students walk out of my classroom this month, I could care less whether or not they have memorized the presidents of the United States (although, that would be nice). My hope is that through the pictures I show of Taiwan, Thailand, and Rome, through the skills we use, through the diverse perspectives we share and the community we build, my students will have the skills that I was given through my TCK background, and with those skills be able to navigate the world.

Featured image courtesy of bluesquarething on Flickr.