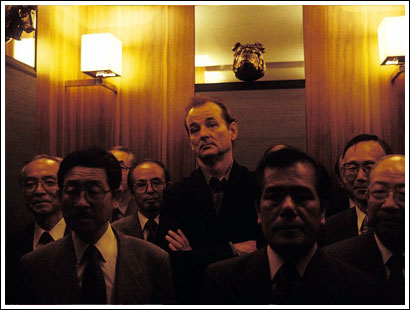

How is it possible to live abroad, without ever really living abroad at all?

Most TCKs have spent some portion of their life in an expat community. These havens from culture shock are a staple in any modern metropolis, isolating wealthy expats from their host cities by allowing them to transplant their home culture abroad. This article will focus on American expat communities.

Sarah Whitten, 21, grew up in the expatriate community in Tokyo, Japan. Attending the American school there, she watched expats hang out at the American embassy, eat American food at the bases, enjoy American music and TV, and spend most of their weekends at the Tokyo American Club.

“There are also homats… nice apartments that are geared toward expats only – probably no Japanese families live there,” she said. “Unless the expat family members take interest in the culture and immerse themselves in it, they can completely isolate themselves from it because they have everything they need accessible to live a totally American life.”

Andrew McWilliam, 20, an expatriate who went to the International School of Dusseldorf in Germany and considers Australia home, said that while he lived among Germans, expatriate institutions still created his social network.

“We lived in a local neighborhood, but we didn’t do anything with the people in the neighborhood,” he said. “We already had a friend base in our community – I would say most of my friends were from the international school.”

[Read Expat Institutions: International Schools]

Host countries are not always welcoming to expatriates, and that can also create barriers.

“Expats come and go, so there’s really no attempt by the locals to reach out, and for good reason,” said Rich Duncombe, a Hewlett-Packard businessman who was an expatriate in Singapore.

Creating a social network with locals in the city was hard because he was always on the move, he said. He only remembers meeting the families of two of his local colleagues.

Unlike immigrant societies, which are “secluded”, expatriate communities are “exclusive,” writes Eric Cohen in Current Sociology. They deliberately maintain closed social networks separate from the host city. However, as expatriates migrate from one city to another, connections are drawn between expatriate communities all over the world. As a result, these communities actually have very open, global networks – albeit exclusive within one type of people. It’s a global, social network that only exists in expatriate communities across the world.

“An expat community tends to be an expat community wherever you go,” McWilliams said. Besides living in Dusseldorf, he has also lived in Ho Chi Minh City in Vietnam. “It’s made up of people not strongly tied to any particular country, and they’re used to traveling. The expatriate community becomes naturally cliquey – it’s isolated from the world.”

Unfortunately, these isolated neighborhoods simply result in creating a sudden, new, remote class of elites within a host city. Local communities can look at these expatriate communities in two ways.

“At best, they are rather patronizingly described as outposts of suburbia, U.S.A. At worst, one gets the impression that they are “golden ghettoes” inhabited by ultra-ethnocentric Yankees who crassly flaunt material wealth in the faces of contemptible (and contemptuous) natives,” writes Harvey Upchurch, author of Towards the Study of Communities of Americans Overseas.

“Generally, locals don’t have a good impression of the expatriate community,” Stephanie Tang said. She is a Malaysian-Chinese who entered the American expatriate community of Singapore at age 9.

“Number one, they think they are a bit rowdy. What they see is the drunken-high school ambling around the road, and the taxi driver being shouted at. Two, they see the expat community as richer: the clothes they wear, the up-market places they shop, being part of the elite American club. Three, they see us as more educated. Four, there is a ‘white’ kind of subtle superiority.”

According to Erik Cohen’s study of expatriate societies, most expatriates’ interaction with locals is much like an interaction of a tourist; they will form acquaintance relationships with chauffeurs, servants, gardeners and cooks, but rarely will they form immediate friendships. In return, there is widespread, covert resentment of the expats in the city.

“Expatriate superiority, coupled with exclusiveness, does not endear them to their hosts,” Cohen writes. “Expatriates are suffered, needed but not beloved.”

Expatriates are needed: They contribute to the local economy, pumping in foreign dollars through investments and spending in the local service industries. But Cohen also writes that the locals treat expats with “ambivalence.” To the locals, the transient expatriates present no real threat. They don’t do much else beyond exist spatially in their environment. Therefore, expatriate neighborhoods, while they create an unwanted, yet tolerable class of elites, only really impact their environments through economic influence.

The Straits Times, the major local newspaper in Singapore wrote a feature titled “Little America” in September 2000. The writer, Loh Keng Fatt, emphasized the intense economic impact and sparse cultural impact the Americans had on the locals. ”Though the [American] landed enclave is only a road away from the HDB flats [local residences] in Woodlands Avenue 1… the expatriates and Singaporeans live separate lives,” he wrote. “Says sales executive Sharon Lee: ‘They seldom come to the shops or hawker centre because it’s hot and maybe not so clean.’”

Loh also wrote that the locals spawned businesses living off the wealthy expatriate community. ”At the Woodgrove mall, some along the 20-odd tenants have got-used to another thing – giving what the expatriates want. So, Ms. Elizabeth Roe stocks her Sports Grove shop with Spalding basketballs, bikes and swimwear. She says that [expatriates] make up 50 percent of the business.”

The relationship between expatriate communities and their host cities is complex. On the economic level, these centers of capitalism draw in expatriate businessmen, hoping to take advantage of foreign investments and skills. Local and foreign economies become intertwined, feeding the global market. Yet on the cultural level, these communities never integrate with their host city. They remain elite, isolated islands of expatriates who, at worst, are the subjects of covert disdain by the local people, and at best, are treated with ambivalence.

In today’s global cities, expatriates are a new kind of temporary migrant. They are needed as connections between the global cities and the global economy. In the past, both city and immigrant group would slowly merge over time. Yet in this new era of global mobility, expatriates move in and out of cities year after year, never having the opportunity to grow into the host culture. They erect institutions and continually live within a closed social network, forming their own exclusive communities.

Therefore, although global cities attract and rely on the expatriate community economically, these isolated islands will never truly assimilate as “part of” the city.

———————————————

Expat institutions: American schools

One of the most important institutions in an expatriate community is the school. American international schools are usually based on an American curriculum and are taught in American English. Among the students, there’s usually a high percentage of U.S. citizens as well as a mix of other nationalities. According to the U.S. Department of State’s Office of Overseas Schools, there are 29,045 U.S. citizens enrolled in 194 international schools in 134 countries. For example, at the Cairo American College in Egypt, one of the larger international K-12 school, about half of the 1,400 students are U.S. citizens [PDF]. Admissions policies at American international schools usually give first and second priority to American citizens and employees of American businesses or organizations. Schools and other such American institutions reinforce the closed social network in expatriate communities.

Increasingly, these international schools are closely tied to international corporations, the organizations that send Americans abroad. For example, on Cairo American College’s 11-person Board of Trustees, there are representatives from oil firms BP/Amoco and Apache Egypt Companies. Furthermore, the U.S. Department of State’s Overseas Schools Advisory Council, which aims to promote and maintain international schools, has many corporate connections. The council is headed by senior executives from America Online, ExxonMobil, General Electric, IBM, Microsoft, PricewaterhouseCoopers, Proctor & Gamble and twelve other corporations. By making schools attractive, they can make living abroad more appealing to American businessmen.

Uncle’s little Asian protege does pretty well!

I’m totally digging this site. Pretty cool, and relevant as well.

Need writers? I’m down.

LikeLike

Pingback: You’re so isolated! Expat communities explained. « Official mkPLANET Blog