I stood on the auditorium stage, momentarily paralyzed. I was trying to scrounge for some sort of intelligent answer to my professor’s query.

“One more question,” he had asked nonchalantly, after I finished presenting the paper I had spent two months working on. “Based on your research, do you think that historians and we as Americans should hold a better view of President Nixon and credit him with doing more for the country as a whole than we do now?”

I had just argued that Nixon’s move to initiate relations with China symbolized a re-envisioning of foreign policy that was critical during that era of American history.

The obvious answer seemed to be yes. Because of Nixon’s adamant steps toward U.S.-Chinese reconciliation, the United States had ceased to base its foreign policy primarily in Cold War terms and began to look instead at strategic advances that foreign relations might hold. This, in general, seemed to be a good thing.

But something stopped me from blurting that answer. “You mean, me personally?” I asked my professor.

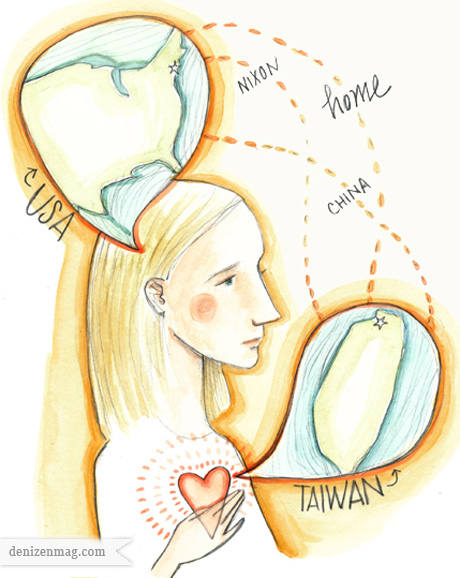

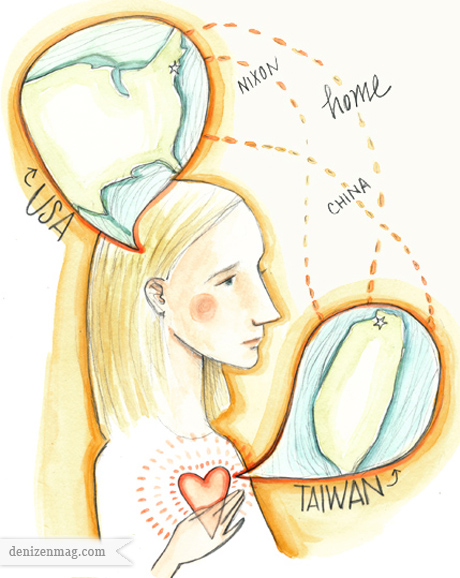

Illustration for Denizen by Mary Lundquist

“Well, yeah,” he replied, a little confused by my response.

Still, I hesitated. I realized that I would feel guilty for voicing support for Nixon. This guilt stemmed not from scorning the criminal acts that Nixon engaged in later on in his presidential career. Rather, it came from a feeling of sudden patriotism for Taiwan, the country of my birth. It’s a country that the United States has not officially recognized since the 1970’s. Because of Nixon. By condoning the actions of President Nixon, I felt that I would, in a sense, be betraying the country that I had spent ninety percent of my childhood in.

The decision seemed insignificant, and I knew what the right answer had to be, but in those moments, I felt two parts of myself conflict more vividly and tangibly than they had in many, many months. A simple classroom question suddenly became a personal question of patriotism.

On the one side, my life as a TCK growing up in Taiwan flashed before my eyes—the way that I felt more comfortable in a crowd of Asians than a crowd of Caucasians; the way that on official documents I had to try Taiwan, Republic of China, or R.O.C. before finally realizing that in the United States’ eyes, I was born in China; the way that I’d gotten so excited when I saw the Taiwan flag in Vatican City because it was one of the thirty-some countries that recognized my country of birth.

On the other side, though, stood my American passport, my blonde hair and blue eyes, my East coast accent, and the assumption that I, like nearly every other American in attendance at my college, saw the United States as the best thing that could even happen to the world.

And then, somewhere in the middle of my two conflicted identities, sat the two months of research that I had done for this paper. The dusty volumes of Foreign Relations of the United States articles still sat on my desk in my dorm room. My twenty-page paper saved in multiple drafts on my computer seemed to scream at me. This was the hard evidence, all of which pointed to the answer being yes, that Nixon’s decision to open relations with China—and thus neglect the United States’ promises to my country of Taiwan—were advantageous for the United States, and as a result greatly benefited America in the long run.

I looked at my professor. “Personally,” I told him, “I’m not a fan of the way Nixon switched recognition to the PRC for personal reasons.” A couple of chuckles from friends who knew me came from the audience. “But at the same time, I do think that Nixon pursued some policies in this situation that were beneficial for the United States, and so in this sense, the answer to your question is yes.”

I had never realized that separating my personal allegiances from research could be so difficult. It was a separation that American students probably wouldn’t have had to make. But for me, it made me realize that TCKs have a distinct advantage in the world, a broader global perspective. I can have a discussion, be able to consider another viewpoint, and yet still be able to keep my own views intact. May we continue to think objectively, and seek to understand others’ perspectives, be they cultural or personal.

I’m so glad to hear others struggle with issues of patriotism also. I was raised in Mexico which makes it hard living in the United States now and hearing people speak about immigration issues. I am a U.S. citizen but I am torn between my two countries; I feel more connected to Mexico.

LikeLike

I grew up in several African countries, so I can relate as well. The recent Kony 2012 debacle had me up in arms and my white friends and family couldn’t understand why, thinking I was just being cynical and unwilling to help.

LikeLike

I’m an international student in the US. I have to say it was quite interesting learning about the Cold War from an American perspective.

LikeLike